Protest: Hope actualized

ICE protests in Paramount, California

And the King will say, ‘I tell you the truth, when you did it to one of the least of these my brothers and sisters, you were doing it to me!’ (Mt 25:40 NLT)

"Sin is when we misuse our God-given agency to project our own will onto history without regard for God's vision."--Karen R. Keen in The Word of a Humble God

The history of the United States has been shaped by protest. Cultural or societal change rarely happens because societies simply feel it's time to change. Fredrick Douglass infamously stated that "Power concedes nothing without a demand. It never did and never will." In a political sense, organized protests amplify voices that are largely ignored by those in power. Using that lens, the march on Washington in 1963 was not the context for a powerful speech by Martin Luther King Jr, but the power of millions of voices gathered to speak collectively, leveraging moral outrage against systems, policies, and behaviors that resulted in cruelty, dehumanization, and violence. The effectiveness of the action was magnified by the diversity; ethnically, culturally, and politically, of those who united for fundamental human rights for one another. The key to the power of the movement was the solidarity of its participants, not only in the clarity of the change needed, but also in the deep connectedness of caring for one's neighbor.

Sixty-plus years later, we have seen global protests against police brutality and now, most recently, protests against the Federal government for its immigration policies. The past protests, such as civil rights, women's rights, workers' rights, and the abolition of slavery, were driven and collaborated with the church. Interestingly, the portion of the church active in these movements was often not the largest or most well-respected (by other churches) churches and denominations. Anabaptists in their peace initiatives, or the historical Black church's modeling of resistance, were leading from the margins, using their collective assets to protest. This contrasts with contemporary protests, which are condemned mainly by the Evangelical Churches in the US.

Part of the impaired vision of anti-protest churches stems from a lack of theological imagination, or what the Late Dr. Walter Brueggemann describes as the "Prophetic Imagination." This is the ability to understand God's purposes in complex situations. When we put God in a box or recreate God as a reflection of our own image, we become unable to see or sense God's purposes in complex situations. Compounding this disability are the partisan lenses that have co-opted the church's power of discernment.

Prophetic imagination is the ability to see God's purposes as revealed in a myriad of possibilities. Most people understand the prophetic impulse of God's Spirit as that which points out sin and is problem-focused. However, the prophetic impulse actually seeks to align people with God's purposes, which ultimately requires a pivot from current practices and perspectives to one capable of beholding the possibilities that honor God.

"Prophetic imagination occurs at the intersection of criticality--a sense of the world's hurt, its pain--and hope--a sense of the world's possibilities, and promises."-- Marshall Ganz in People, Power, Change

Indeed, it is not simply considering the possibilities but surrendering to God's purposes and being agents of the possibilities God seeks. Hope is not simply optimism or positivity. Hope is the confidence in a divine response to our situation. Hope in the Christian faith is represented by the resurrection of Jesus. In the resurrection, we have divine intervention that aligns with God purposes. In the midst of death and despair, Jesus came back from the dead. Like Jesus, his followers will also undergo pain and suffering, but understand that there are divine possibilities for a life that overcomes the forces of death, injustice and violence.

"Resurrection hope is not to be confused with blind optimism or wishful thinking, just as lament is not the same thing as despair or desperation. Hope means not conforming ourselves to an unjust reality, but rather imagining possibilities for transformation."--Nancy Elizabeth Bedford in Who was Jesus and What Does It Mean to Follow Him?

Jesus is not silent regarding the suffering and pain of others. In his last parable in the book of Matthew (Mt 25:31-46), he speaks of a day when people are judged by how they have lived. He bases the decision on how people treated those who were hungry, without shelter, without clothing, and incarcerated. His judgment was based upon his standard of ethics, which is love for God and being a loving neighbor to those around you, without condition.

Inherent in this parable is the view from those who were helped. Those whom Jesus called the sheep (and who were awarded eternal life) were the answer to the prayers of the desperate. They were agents of hope (Divine intervention amid adversity). They did not love their neighbors conceptually, but pragmatically and in solidarity, entered their suffering and advocated for them. We do not know if the hungry, thirsty, estranged, naked, sick, and incarcerated were good or bad people, but the radicality of the great commandment is that it loves for the sake of a God who describes Godself as love. Jesus didn't restrict loving to a nationality, ethnicity, political identity, gender, sexual orientation, or socioeconomic status.

The response of Christians against protests, without understanding the genesis for the protest, becomes what Historian Jemar Tisby calls "Complicit Christianity". Complicit Christianity "forfeits its moral authority by devaluing the image of God in others." It employs different means to do this. Rarely do Christian leaders say "Other people matter less," but their unwillingness to advocate against injustice as if it were themselves is disobedience to the great commandment to love God with everything you are and to love your neighbor as yourself. While it is impossible to advocate for everything unjust, those within our sphere of influence and identity are.

One of the problems in the American Evangelical church is that we minister and read the Bible through our privilege. Privilege in itself is a neutral term. Privilege speaks to access to resources that allow you to thrive. Those resources, such as safe neighborhoods, quality schools, drinkable water, and affordable food, become an entitlement to those with privilege and out of reach for those without. When that privilege is based upon something inherent, like ethnicity or gender, then privilege becomes a tool of inequity to others outside of the privileged class. In the United States, privilege is mainly understood through ethnicity (whiteness) and gender (maleness). However, there are many others such as nationality, social economic status, exclusive neighborhoods (if you ever want to see educational disparities, sort SAT scores by zip code), and sexual orientation (heteronormative). These privileged classes become the standard of what is "us," and the non-privileged people become "them". There is a natural impulse to protect and promote "us" and a natural suspiciousness of "them". Dr. Korie Edwards (Estranged Pioneers, 2022) states that privilege is maintained by personal preferences and systemic advantage, entitlements, and power. I have oversimplified privilege, as there is a massive intersection of multiple types of privilege that are not simply additive, but unique. For example, job applications with similar backgrounds are treated differently by ethnicity, gender, and gendered ethnicity. This is why those often on the margins of our society tend to better understand God's prophetic impulses, because they have borne the brunt of the inequity.

The Bible is written to communities who were often oppressed and struggling. New Testament Theologian Mitzi Smith (Insights from African American Interpretation, 2017) states that "reading the Bible has always been and continues to be both a political and a theological undertaking." Within communities that are privileged and prize individualism, understanding a communal document directed at the underprivileged.

"Here is the critical question: Is it possible for someone who lives, breathes, and interprets Scripture from the social location of empire to understand a book written entirely from the underside of empire--written by and for oppressed people?"--Lisa Sharon Harper in Still Evangelical

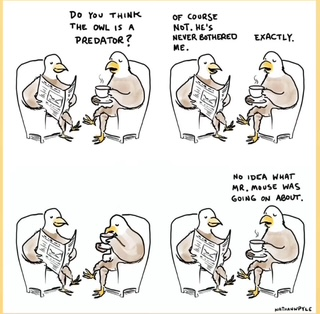

Privilege and its effects are hard to understand for many who are privileged. Because privilege is normative, it becomes like air, which is appreciated but not seen. I came across this cartoon that helped me think about it more simply:

In this picture, the eagles cannot imagine that the owl is a predator because the owl does not behave in a predatory manner towards them. But the mouse, which is one of the dietary preferences of the owl, only knows the owl as a predator. The eagles in this comic have a privilege that prevents them from seeing the problem that the mouse faces daily.

The result of seeing protest primarily from privilege is that we are only interested in the God-purposed possibilities that protect our privilege. Former Christianity Today Editor Kaitlyn Schiess (The Liturgy of Politics, 2019) states, "Political uninterest thrives in places of privilege." What she is stating is that many churches wave a banner of avoiding politics, mainly because the current system supports their privilege. This apolitical insistence also warps our theological imagination, as it cleaves the essential matters of the spirit from the crucial aspects of the body and society. This is not a new phenomenon. The entire prophetic movement of the Hebrew Scripture (Old Testament) points out God's intolerance for a disembodied religiosity.

"This was the primary message of the biblical prophets; religiosity is not an acceptable alternative to doing the works of righteousness and justice."--Marvin McMickle in Let the Oppressed Go Free

By supporting public protests where there is injustice, participate in God's acts of loving-kindness, justice, and righteousness (Jer 9:23-24). Protesting against injustice embodies Jesus' admonition to be shalom-makers in our community (Mt 5:9). Our approach to protest in advocacy should be cruciform, meaning it is modeled by Jesus' approach to the cross, which is non-violent and sacrificial. Almost all leaders of justice-informed Christian ministries will tell you that there is a heavy price to be paid for standing for truth and dignity.

"Is it possible that we all love compassion and justice until there's a personal cost to living compassionately, loving mercy, and seeking justice?"--Eugene Cho in Overrated

Jesus said that if anyone would follow him, we would need to deny ourselves, pick up our crosses, and follow him (Mk 8:34). While clearly articulating the call towards being sacrificial agents of hope, Jesus was also giving insights into our own transformational journey that occurs when we advocate for others. Again, Rev Eugene Cho helps us understand:

"Oftentimes, we go about our concept of justice or compassion or generosity when it is about us and our power and privilege to do something for others, without entertaining the possibility that maybe God wants to change us."--Eugene Cho in Overrated

One of the justifications that is used for inactivity or antagonism against protests of injustice, is inaccurate readings of scripture. Romans 13:1-7 is frequently used to dissuade the people from protesting against the government, no matter how immoral or unjust the government is.

Everyone must submit to governing authorities. For all authority comes from God, and those in positions of authority have been placed there by God. 2 So anyone who rebels against authority is rebelling against what God has instituted, and they will be punished. 3 For the authorities do not strike fear in people who are doing right, but in those who are doing wrong. Would you like to live without fear of the authorities? Do what is right, and they will honor you. 4 The authorities are God’s servants, sent for your good. But if you are doing wrong, of course, you should be afraid, for they have the power to punish you. They are God’s servants, sent for the very purpose of punishing those who do what is wrong. 5 So you must submit to them, not only to avoid punishment, but also to keep a clear conscience. (Romans 13:-5 NLT)

Seems like it says plainly that the Roman Emperor and the Roman soldiers are "God's servants, sent for your good, all governments (authorities) are put in place by God and that we should submit because its akin to submitting to God. I do not have the space to give all the nuance to this text, but allow me to place a couple of points that allow you to understand the context of this scripture:

1. Paul is writing this from prison, where he was placed unjustly. He does not believe that the Roman Emperor and the Roman soldiers are "God's servants, sent for your good," as he has lived under the cruel oppression of Rome his entire life. He also understood that Roman authorities not only crucified Jesus but also persecuted Christians, which he was experiencing.

2. Paul himself caused riots everywhere he went for preaching the good news. He violated local laws regarding pagan devotion and did so in good conscience. The early church continually chose whether it was appropriate to serve the ways of man or God (Acts 4:19). The way of man was often in the form of human governments.

3. If you have ever corresponded with someone who is incarcerated, you know that your letter and its response are read by the prison officials. Some scholars believe that he added this section to his letter so that it would not be seen as threatening. This makes sense, as I believe the original readers, who lived under Roman oppression, recognized that Rome was definitely not the servant of God, as it killed and brutalized the followers of Jesus.

All of that to say: God is looking for people to be agents of living hope among people who are suffering. Jesus wants us to honor government only to the extent that it does not impinge upon God's life-giving, liberating, and loving purposes. This is the radical dimension of the great commandment and the countercultural community devoted to Jesus and his mission to bear the image of God and extend the actions of a God who acts in loving-kindness, justice, and righteousness. That means we err on the side of bringing shalom and advocating for the victims of injustice.

I leave you with a quote from Sociologist Shawn Ginwright (The Four Pivots, 2022):

"Social change is fundamentally about individual and collective responsibility for creating, imagining, and relating together in new ways. Self-reflection is a commitment to a process and a way of seeing the world that is an interconnected whole, rather than individual cogs in a machine."

I pray that you live out your journey as living hope, promoting an expansive possibility based on God's purposes. Using that lens to understand protests changes everything.

Comments

Post a Comment